The region of Emilia-Romagna in Northern Italy prides itself on its contributions to cinema. From a website promoting tourism in the region: “Emilia-Romagna has always had a strong cinematographic tradition, with a place of honour in the history of cinema for having spawned major filmmakers like Michelangelo Antonioni, Federico Fellini, Tonino Guerra, Cesare Zavattini, Bernardo Bertolucci, Pier Paolo Pisolini [sic], Valerio Zurlini, Pupi Avati, Florestano Vancini and Liliana Cavani.”

Naturally, for the Emilia-Romagna tourism board these names are nothing but ornaments. The irreverent temperaments and iconoclastic impulses of Fellini, Pasolini, and Bertolucci are well known, and there are other transgressive figures among those listed who would scoff at being held up as exemplars of their region’s cultural heritage. Liliana Cavani was branded an enemy of the church when her early Galileo biopic was banned by the Italian authorities, and reviled even more for the Nazi eroticism in The Night Porter a few years later. Why is old-guard communist Valerio Zurlini included? Probably not because of his forgotten anticolonial prison film Seduto alla sua destra (released in the US as Black Jesus and retitled Super Brother for a VHS release) about Patrice Lumumba’s capture and torture by the Belgian authorities. The tourism bureau omitted Marco Bellocchio from its list, maybe because they forgot about him, or maybe because the intense anticlericalism and Maoism of his early films, such as China is Near and Long Live Red Proletarian May Day, make him an unsavory figure.

It is these three punks and pranksters, these black sheep and street-urchins, these thorns in the side of self-respecting Italian society whom the Spectacle Theater wishes to present to you, but through an entirely different set of films than those mentioned above. Liliana Cavani’s I Cannibali presents us with a near-future Milan where radicals are being killed in the street left and right, and exceptional legislation is passed to prevent their burial. Valerio Zurlini’s Desert of the Tartars in turn buries us in the absurdity of an imperial military outpost paralyzed by an eternal expectation of barbarian invasion, an obscure threat that is never realized. Marco Bellocchio’s In the Name of the Father is an Italian If… in which a Catholic boarding school and its administration are thoroughly disrespected and ridiculed by an utterly ungovernable student body led by a coldly calculating vanguard, and paternal authority in all its guises is literally slapped around from the first minute onward. Finally, Bellocchio’s Slap the Monster on Page One brings us back to Milan, where the streets are illuminated by erupting petrol bombs, and where student protesters, militant workers, and leftists of all stripes are being systematically criminalized by a powerful right-wing sensationalist newspaper helmed by an inscrutable but ultimately impotent Gian Maria Volonté.

THE YEAR OF THE CANNIBALS

THE YEAR OF THE CANNIBALS

a.k.a. I cannibali

Dir. Liliana Cavani, 1969

Italy, 95 mins.

In Italian with English subtitles.

SUNDAY, JANUARY 5 – 5:00 PM

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 22 – 10:00 PM

Liliana Cavani is probably best known for her portrayal of a complex erotic relationship between a former SS officer and a concentration camp survivor in her 1974 film The Night Porter. Largely overlooked however is her 1969 feature, The Year of the Cannibals, which investigates a different kind of obscene authority and the “natural rebellion” it provokes.

In this loose adaptation of Antigone set in a near-future Milan, the State has forbidden the removal of the bodies of rebels that litter the streets. As a result, the corpses are stepped over and ignored by the citizens, reminding us how a comfortable private existence in the metropolis everywhere means turning a blind eye to misery. Britt Ekland (The Man with the Golden Gun) and Pierre Clémenti (Pigsty, The Conformist) band together as vigilante body-snatchers in defiance of the decree, and ultimately face repression and execution. A radical chic romp that recalls A Hard Day’s Night and Clémenti’s work with Groupe Zanzibar, The Year of the Cannibals also offers a sober early analysis of the notorious “years of lead” in Italy, characterized by witch-hunts and wholesale incarceration of suspected militants.

“I intended to use the language of myth and universal symbols to avoid the revolutionary speeches that had become a cliché by 1969-1970. … [The Year of the Cannibals] is not the chronicle of a revolution, … but the spectral analysis of reality beyond the various episodes that characterized the demonstrations. I believe it is a comprehensive analysis, and primarily a discourse of generations.”

-Interview in Écran #26, June 1974

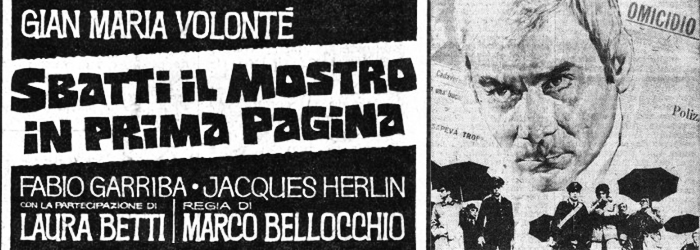

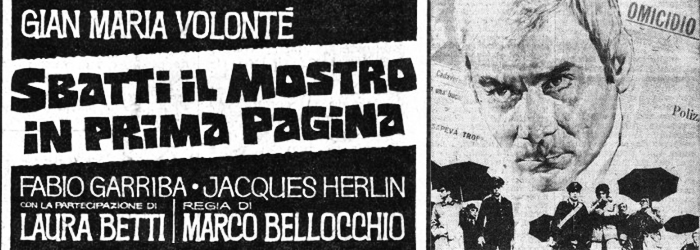

SLAP THE MONSTER ON PAGE ONE

SLAP THE MONSTER ON PAGE ONE

a.k.a. Sbatti il mostro in prima pagina

Dir. Marco Bellocchio, 1972

Italy, 90 mins.

In Italian with English subtitles.

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 8 – 7:30 PM

SUNDAY, JANUARY 19 – 5:00 PM

MONDAY, JANUARY 20 – 10:00 PM

At Il Giornale, Milan’s equivalent of The New York Post, editor-in-chief Gian Maria Volonté is in charge of engineering the headlines for maximum effect: A story about a self-immolation is sensitive material (“You can’t say ‘desperate’ and ‘unemployed’ … It’s a provocation!”) and has to be dealt with tactfully (“Dramatic Suicide of an Immigrant”), while criminal fanatics should be treated with the utmost severity (“The Circle is Closed: Fascists and Left Extremists United by TNT“).

When a high school student is found strangled in the woods, Volonté’s misinformation machine kicks into high gear to mythologize her as the very image of saintly innocence and chastity and to cast her classmates as a diabolical anarcho-Maoist conspiracy bent on chaos and corruption. With the elections closing in, a mysterious Christian Democrat candidate controls the newspaper’s editorial direction remotely from his kitsch-baroque office, engineering a defensive mass-hysteria over red guerrillas and provocateurs lurking in the shadows and threatening to dismantle civilization by force of Molotov cocktails and rock-n-roll.

Made in the early years of the massive proletarian and youth movements that erupted in Italy in the late 60s, Slap the Monster on Page One is both a partisan self-critique and a response to the climate of fear and repression generated by the reaction.

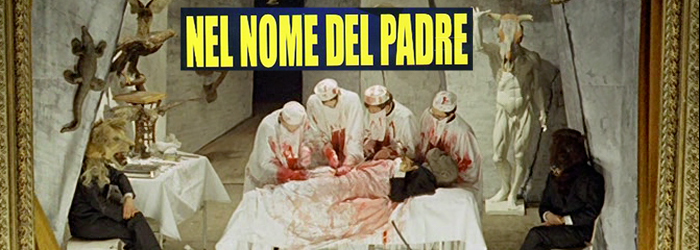

IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER

IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER

a.k.a. Nel nome del padre

Dir. Marco Bellocchio, 1971

Italy, 115 mins.

In Italian with English subtitles.

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 8 – 10:00 PM

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 22 – 7:30 PM

“To ridicule, with farcical overtones, the hypocrisy of our religious institutions and their representatives: the confessors, the exorcists, the spiritual terrorists, those specialists in the fear of God, always trying to traumatize us. We hope that the audience will erupt in a liberating laugh, managing to be ironical about their own fears, their existential traumas! I wish I had the power to erase all priests and all churches!”

This could be a description of Bellocchio’s purpose in making In The Name of the Father, but it is spoken by Franco, a student at an unnamed Catholic boarding school where he—as part of a small intellectual vanguard—hopes to incite the rest of the already insubordinate student body to open rebellion. Another member, the rigorous and aristocratic Transeunti, is desperate to overcome the paralyzing mediocrity he sees permeating the school, and dreams of restoring a decaying institution whose former authority and social significance have almost completely eroded with the expansion of capitalist social relations and their norm-liquidating power.

The conflict between the administration and the students is supplemented by that between the students and the kitchen staff, a group of marginals, invalids, and former drunks whom the school has given the chance to redeem themselves through labor. Lou Castel, the star of Bellocchio’s debut feature Fists in the Pocket, is foremost among them in antagonizing the bourgeois students, spitting in their soup and sabotaging Franco and Transeunti’s didactic play.

Never before has paternal authority been so thoroughly discredited and revealed in its impotence. Dads, priests, wardens, and even God himself get their share of contempt heaped on them. In a scene reminiscent of the most beautiful shot in Jean Vigo’s Zero for Conduct, the boys in single file march up to a bust of the school’s founder and hawk loogies at him, drenching his face in mucus in slow motion.

THE DESERT OF THE TARTARS

a.k.a. Il deserto dei tartari

Dir. Valerio Zurlini, 1976

Italy, 140 mins.

In Italian with English subtitles.

SUNDAY, JANUARY 5 – 7:30 PM

SUNDAY, JANUARY 19 – 7:30 PM

“The older a nation’s history is, the more legends spring up. In the end, we don’t know what’s true and what isn’t.”

Largely overlooked director Valerio Zurlini’s The Desert of the Tartars is an allegory of the disintegration of Empire.

It is 1901. Lieutenant Drogo (played by frequent Costa-Gavras collaborator Jacques Perrin) graduates from the military academy and is immediately dispatched to the most remote fortress on the northern border of an unnamed empire to guard against a mythical impending barbarian invasion. The only sign of human presence in the desert beyond the border has been a group of mysterious horsemen glimpsed fifteen years prior by Captain Hortiz (Bergman favorite and exorcist Max von Sydow), and the only officer who has seen any action is the ancient and distinguished Colonel Nathanson (Fernando Rey of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The French Connection).

Years pass in performing pointless drills, maintaining the most painstaking decorum, and undertaking futile land-surveying missions in the surrounding desolation. Doctor Rovin (Jean-Louis Trintignant of The Conformist, My Night at Maude’s, and Z) has discovered rare bacteria living in the fortress’s walls, which ultimately lead to Lieutenant Drogo’s ill health and pathetic withdrawal from the fortress.

Described as “the grandest and most lavish existentialist parable ever made” (Michael Atkinson, The Village Voice), The Desert of the Tartars is about the historic necessity of empires to define themselves in opposition to an external threat, and the inevitable autoimmunitary destruction that threatens them from within.

THE GERMAN SISTERS

THE GERMAN SISTERS

THE YEAR OF THE CANNIBALS

THE YEAR OF THE CANNIBALS SLAP THE MONSTER ON PAGE ONE

SLAP THE MONSTER ON PAGE ONE IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER

IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER

BONNIE’S KIDS

BONNIE’S KIDS