Of the filmmakers associated with the so-called New Swiss Cinema, itself not particularly well-known abroad, Michel Soutter has perhaps the least claim to being any kind of household name. Alain Tanner and Claude Goretta are known outside their homeland, but Soutter has largely remained what he consciously started out as: a provincial filmmaker. Throughout his three-decade long career he stuck to the region between Geneva and Fribourg, setting all his films in the cities and their immediate environs. This geographical intimacy translates to a personal intimacy. His main focus is always the little particularities and material details of the lives of his characters, the clothes they wear and the furnishings in their houses. But what makes Soutter interesting is not the mere documentary value of his films—the immortalization of various minutiae of life in the provinces—but the purposes he uses it for: denouncing the spiritual vacuity of the Swiss bourgeoisie, finding value in idle playfulness, and lending his voice to a frustrated generation of directionless rebels who rattle their golden fetters if not actually breaking through them.

In his later films Soutter would go on to collaborate with such well-known figures of French cinema as Jean-Louis Trintignant, Delphine Seyrig, and Pierre Clémenti, but in his early works he employed such home-bred talent as Jean-Luc Bideau, who also worked frequently with Tanner and Goretta. This series of Soutter’s first five features aims to highlight the charming modesty of his themes, his economy of means, and the subterranean force running through the apparent calmness of his work: the schizophrenic boredom of the Swiss, which makes the restless among them leap from one though to another arbitrarily, poetically, trying to learn to feel again by feigning joy and rage and dispassionately emulating real passions.

THE MOON WITH TEETH

a.k.a. La Lune avec les dents

Dir. Michel Soutter, 1966

Switzerland, 75 min.

In French with English subtitles

SATURDAY, AUGUST 1 – 7:30 PM

THURSDAY, AUGUST 6 – 7:30 PM

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 26 – 10:00 PM

“I was twenty. I won’t let anyone say it’s the most beautiful time of life.”

The first line of Sartre’s schoolmate and Resistance fighter Paul Nizan’s 1931 novella, Aden-Arabie, is echoed by William, the young and restless subject of Soutter’s first feature. William lives an uprooted life, structured by a worthless bowling alley job and punctuated by self-destructive binges. He’s the first of Soutter’s lonely rebel protagonists, young men with deep reserves of undirected energy and shapeless yearnings for liberation. He’s virile, brooding, and violent. He regards children, virginity, and love as weaknesses. With his materialistic nihilism, it’s as if he was picked straight out of a Dostoevsky novel: “You know how science defines life? Gradual degeneration culminating in death.”

William’s terminal dissatisfaction derives from that other major theme of Soutter’s: Swiss society. In his films, the Swiss are either content professionals and housewives or quarrelsome misfits without any positive vision of the ultimate upheaval that would deliver them from the airless luxury prison that Switzerland represents for them. Shoplifting out of boredom, William resorts to a typically Swiss argument when caught: “I was trying to economize.”

HASCHISCH

Dir. Michel Soutter, 1968

Switzerland, 77 min.

In French with English subtitles

SATURDAY, AUGUST 1 – 10:00 PM

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 12 – 7:30 PM

SUNDAY, AUGUST 23 – 5:00 PM

Soutter’s second feature fared better with the critics. At the very least, it showed the director’s mettle to continue building on his main preoccupations—feckless, aimless youth, absence of political solidarity and the anemic qualities of Swiss society—that had been the subject of so much initial derision. Like William in LA LUNE AVEC LES DENTS, Mathieu is another disciple of dissatisfaction trudging through everyday life. “Living together gets boring. We just save money,” says his friend, Bruno. An actor of the theater, Mathieu has few prospects in this trade, save for empty promises from his producer. At this point, he’s more a kind of flaneur—only, his sojourns don’t occur along the boulevards and arcades of Baudelaire’s Paris, but on the sterile streets of a nondescript town. All is bleak morass. Frustrated with his work in the theater, Mathieu decides he wants out of Switzerland. Matthew asks Bruno, a car mechanic, if he wants to split for Anatolia. Bruno agrees, breakups with his girlfriend and spiffs up his car. Meanwhile, Mathieu must pick up a theater friend, Pauline, an actress of note, from the airport. Naturally, Mathieu falls in love with her, and suddenly, leaving for Anatolia becomes all the more difficult.

In HASCHISCH, there aren’t any scenes of drugged-out dope fiends, but the title’s narcotic connotations run true throughout the film: Soutter captures his actors deep in the haze of their own private worlds as they walk through an unconvincing reality, one which always depresses the shoulders and dulls the mind (Pauline: “Good thing we don’t think!”). Soutter’s characters are always sharply aware of the moribund nature of their lives, but are unable act on their own desire for change. In one scene, Mathieu is in the recording studio and recites, ironically, a few lines by the Turkish poet, Nâzım Hikmet: “I contemplate Switzerland from the train. Her towns are boring but her sanatoriums are gay! Could I live among such respectable folks? Maybe when I’m 90…Why have I written about Switzerland?”

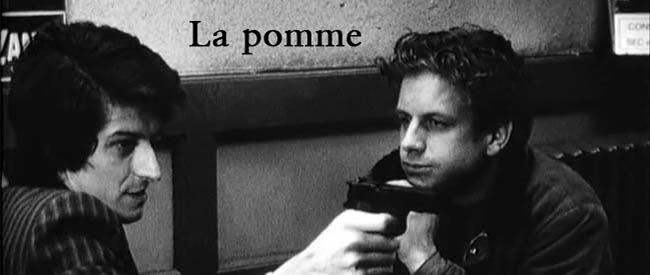

THE APPLE

a.k.a. La Pomme

Dir. Michel Soutter, 1969

Switzerland, 85 min.

In French with English subtitles

SUNDAY, AUGUST 9 – 5:00 PM

SATURDAY, AUGUST 15 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, AUGUST 31 – 7:30 PM

Soutter’s third feature follows a handful of young idlers and professionals in Geneva, living out the kind of sluggish, arbitrary existence that a country as suffocatingly prosperous as Switzerland makes possible. Something of a solitary revolutionary, Simon is mapping out the places in Geneva where Lenin lived in exile before the 1905 uprising. Simon’s boss, Marcel, is a jet-setting reporter and a perfect symbol of Swiss complacency, living in a suburban villa that he calls his “refuge from revolutions, civil wars, crises, and coups d’état.” When Simon’s girlfriend Laura comes to visit, a bitter triangle drama develops among them, as Simon’s hatred for Marcel and the world he represents keeps growing.

THE APPLE has been compared to Jean Eustache’s 1967 short film SANTA CLAUSE HAS BLUE EYES (starring Jean-Pierre Léaud) for its ability to capture all the nuances of both the happiness and the malaise of indecisive adolescents. Beyond that, it offers snapshots of late 1960s Geneva, an acerbic commentary on the self-satisfied, smug inertia of the Swiss bourgeoisie, and an indictment of the journalistic profession. As Simon says, “Switzerland has its ass placed squarely on the Third World,” and Soutter goes to infuriating lengths to convey the stiflingly peaceful postwar atmosphere that its isolated rebels feel a growing urge to break through.

JAMES OU PAS

Dir. Michel Soutter, 1970

Switzerland, 80 min.

In French with English subtitles

MONDAY, AUGUST 10 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, AUGUST 24 – 7:30 PM

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 26 – 7:30 PM

If Soutter steered clear of any attempt to build a plot in his previous features, in JAMES OU PAS, Soutter offers enough dramatic inflections to show a marked change in his practice. As in Antonioni’s BLOW-UP, a witness to a potential act of crime jumpstarts the film. Hearing a gunshot, Hector (played by the irrepressible Jean-Luc Bideau), a low-wage cabdriver, stops his car midway somewhere in the Swiss fields and follows the man he suspects was responsible for the shooting. Instead, Hector runs into James, an enigmatic bachelor who lives all alone in his ivory-tower pad. James convinces him to pick up his friend Eva from the airport, and suddenly Hector—accustomed to a rote schedule—finds himself entangled with a group of strangers in a time and place he does not recognize. Hector’s quandary prompted Jean-Louis Bory to call JAMES OU PAS Soutter’s re-formulation of Hamlet’s “to be or not to be.” More to the point, as Soutter’s most perceptive critic, Freddy Buache, noted, a Soutter film usually boils down to “men and women at the intersection of everywhere and nowhere … brought together in unexpected situations by chance, and they have to unmask or mask themselves, become believable or make-believe, speak to each other, and, intentionally or not, confess to being what they are.”

Soutter’s dry humor finds its perfect mouthpiece in Bideau, who can rattle off monologues with jovial ease. The rotating cast of characters and chance encounters recall some of the fluid cat-and-mouse games of Jacques Rivette. Gone are the Bressonian, stone-faced types from his earlier films. The droll, everyday languorousness of Swiss life still remains in the backdrop, but with Soutter’s newly formed comic lightness, the absurd registers most strongly in JAMES OU PAS. Dazed from the turn of events, Hector, growing increasingly unable to distinguish reality from his own thoughts, says to himself, as if entranced, “I want life to be as it always has been: monotonous and comfortable.” Can anyone escape Soutter’s Swiss Inferno?

THE SURVEYORS

a.k.a. Les Arpenteurs

Dir. Michel Soutter, 1972

Switzerland, 81 min.

In French with English subtitles

MONDAY, AUGUST 3 – 7:30 PM

SATURDAY, AUGUST 8 – 10:00 PM

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 19 – 7:30 PM

In his fifth feature, Soutter breaks his rule of portraying only the idle classes of Swiss society and the equally idle would-be fugitives from it. Leon—a lion of a man with a thick caterpillar mustache and heavy mutton chops—is a land surveyor whose job brings him to the country estate of Alice, a dreamy blonde who picks strawberries in the garden and never misses teatime with her mother. After a fleeting liaison in Alice’s house with a mysterious English woman who disappears as quickly as she appeared, Leon becomes terrified for his own sake (Was she of legal age? Will there be criminal charges? Was I trespassing?) and hires a lawyer to save his skin. An inveterate egoist, Leon’s statement of principle could easily double as a slogan of Swiss isolationism: “We’re never as strong as when we’re alone.”

THE SURVEYORS is firmly implanted in Soutter’s usual milieu of professionals living in the prosperous Swiss countryside, a world of lawyers, cellists, and noncommittally philosophizing young ladies. But here he adds an element of foreboding: the surveyors are invading the provinces, planning to build God knows what awful roads or shopping centers. The gentry are feeling a nebulous panic growing inside them. What will happen to our Switzerland of quaint chalets and verdant hills?