“If the desire of the Nouvelle Vague’s protagonists was to take over the industry and make it more pliable (notably by creating independent economic structures, in the manner of Eric Rohmer and François Truffaut), then the Lettrists’ strategy, by contrast, entailed resisting the least compromise with the film industry, just as with the art market” —Nicole Brenez, Introduction to Lettrist Cinema

Beginning in 1951, Lettrist filmmakers set out to destroy all of cinema’s existing rules. The art movement which sought out chiseled, infinitesimal, and imagined cinema, was short-lived and remains under-researched barring a few key texts by art historians Nicole Brenez and Kaira M. Cabañas. Among its members were Jean Isidore Isou, whose unfinished 9-hour cut of TRAITÉ DE BAVE ET D’ÉTERNITÉ caused a ruckus at the 1951 Cannes Film Festival. Isou’s scratched images and complimentary discordant soundtrack set the tone for future experiments in Lettrist Cinema: Guy Debord weaponized the black-screen in his feature debut HURLEMENTS EN FAVEUR DE SADE (1952), Gil Wolman created a flickering and vanishing film with L’ANTICONCEPT (1952), and François Dufrêne abandoned images altogether by projecting an imaginary film, TAMBOURS DU JUDGEMENT PREMIER (1952).

This September, Spectacle Theater is thrilled to present a small selection of Lettrist films as they were originally intended to be screened. As noted above, Isidore Isou’s TRAITÉ DE BAVE ET D’ÉTERNITÉ remains the most well-known film to come out of the Lettrist Movement, as its sustained lashing out against cinema’s conventions in all manner of offensive aesthetic and narrative gestures have made it a lodestar for filmmakers looking to reimagine the seventh art. Released around the same time is Maurice Lemaître’s LE FILM EST DÉJÀ COMMENCÉ?, a self-destructive instructional film that the director cheekily described as “a boring jumble of commonplace ideas.” HURLEMENTS EN FAVEUR DE SADE and L’ANTICONCEPT continue the Lettrist investigation into a counter-cinema, engaging a negative image that bestows creative authority to the audience. In counterpoint, Marc-Gilbert Guillaumin’s (aka Marc’O) CLOSED VISION (1954) brings together an excess of images in a Joycean attempt at creating a stream-of-consciousness film. In GRIMACE (1967), Gudmundur Gudmundsson Ferro (aka Erró) returns to the Lettrist mission to separate cinema from its stars, stitching together amusing portraits of artists including Andy Warhol and Marguerite Duras into a playful visual poem.

TRAITÉ DE BAVE ET D’ÉTERNITÉ

(VENOM AND ETERNITY)

dir. Isidore Isou, 1951

France. 123 mins.

In French with English subtitles.

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 3 – 5 PM

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 7 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 11 – 7:30 PM

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 29 – 7:30 PM

“Isou turns pictures upside down, scratches on them arbitrarily and does everything he can think of to spit upon and destroy the film image” —Stan Brakhage

To invoke Lettrism is to call on VENOM AND ETERNITY. Also known as SLIME AND ETERNITY, Isidore Isou’s sole feature is a film full of scratches that chisels its way to the beating heart of cinema. “If we can’t get past the photographic screen and reach something deeper, then cinema just doesn’t interest me,” he said. Looking to break away from the regressive sanctification of representation upheld by theorists like André Bazin, Isou’s film revels in its obscene and destructive character, tearing up the traditions of the medium to dream up a new alternative.

After premiering at Cannes Film Festival in 1951 and causing a scandal among festival attendees, VENOM AND ETERNITY was awarded the “Prix des spectateurs d’avant-garde” by Jean Cocteau. The award placed it in the same category as Maya Deren’s similarly lauded MESHES OF THE AFTERNOON (1943), marking it an essential text in the canon of experimental cinema that would have a lasting influence on filmmakers ranging from Jean-Luc Godard to Stan Brakhage. Isou would later remark that Godard and Debord ripped him off.

LE FILM EST DÉJÀ COMMENCÉ?

(HAS THE FILM ALREADY STARTED?)

dir. Maurice Lemaître, 1951

France. 62 mins.

In French with English subtitles.

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 16 – 7:30 PM, this event is $10

After working on Isou’s VENOM AND ETERNITY as an assistant director, Maurice Lemaître set out to make a film that not only attacked the conventions of filmmaking, but of filmgoing too. LE FILM EST DÉJÀ COMMENCÉ? is a film that spills from the screen, as instructed by its script which expands upon the body of the film to include what should occur in the viewing room as it’s projected. Hellbent on provocation, Lemaître thought up LE FILM EST DÉJÀ COMMENCÉ? as a way to shake up the moviegoing experience. Throughout the film, he directly addresses the audience with questions such as “Why are you here?” while they sit in the dark watching the movie also subject to the insults of “extras” taunting their ability to watch the whole thing through.

The film is made up of a series of kaleidoscopic images. Unlike Debord and Wolman, Lemaître stresses the visual quality of his cinema. LE FILM EST DÉJÀ COMMENCÉ? is colorful, fun, and wholly unruly, reflecting the spirit of a passionate young filmmaker meddling with the rules of his craft.

HURLEMENTS EN FAVEUR DE SADE

(HOWLINGS IN FAVOR OF DE SADE)

dir. Guy Debord, 1952

France. 64 mins.

In French with English subtitles.

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 11 – 10 PM

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 21 – 10 PM

In his first film, Guy Debord abandons the photographic image. Over the course of HURLEMENTS EN FAVEUR DE SADE, Debord along with fellow Lettrists Isou, Gil Wolman, Serge Berna, and Barbara Rosenthal speak over each other in aphorisms. The screen is white when they talk and black whenever there is silence. The film’s refusal to represent foretells Debord’s future critiques of image-culture, most notably the text from which this theater derives its name: SOCIETY OF THE SPECTACLE (1967). Eventually, Debord and Wolman would break away from the Lettrist Movement to carry out new acts of detournement as Situationsists. As such, their goals were more directly aligned with a Communist agenda. Yet, in their early works resides a conceptual spark that they would build upon throughout their careers as artists. This would become clearer in a Lettrist bulletin from 1956, in which Wolman declared their objective to be the creation of “a unitary urbanism” that synthesizes “arts and technology” in accordance “with new values of life.”

![]()

L’ANTICONCEPT

(The Anticoncept)

dir. Gil J. Wolman, 1952

France. 60 minutes

In French. An English Transcript will be provided.

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 21 – 7:30 PM, this event is $10

“Wolman is one of the great inventors of negative forms after Hegel” —Nicole Brenez, Introduction to Lettrist Cinema

L’ANTICONCEPT is a sound film that alternates between black and white flickers. The film is projected on a helium-inflated balloon approximately two meters in diameter. A year after the film premiered at the Ciné-Club Avant-Garde 52, Debord declared L’ANTICONCEPT was “more offensive… than the images of Eisenstein, which frightened Europe for so long.” Although the Lettrists shared a proclivity for hyperbole, Debord’s statement accounts for Wolman’s incredible ability to leave behind all of cinema’s precepts and create a frightening alternative to the medium with his film.

CLOSED VISION

dir. Marc’O, 1954

France. 65 mins.

In English.

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 01 – 10:00 PM

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 03 – 7:30 PM

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 09 – 10:00 PM

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 28 – 10:00 PM

Marc-Gilbert Guillaumin aka Marc’O played a major role in the history of Lettrism. With close ties to Jean Cocteau, Marc’O convinced the Cannes Film Festival in 1951 to screen Isidore Isou’s VENOM AND ETERNITY. He similarly organized screenings for his colleagues’ work, encouraging them to adopt new approaches to cinema and agitate audiences in viewing rooms to create more visceral encounters with the medium. Many of his suggestions—aquarium-cinema, aquatic-sports cinema, carousel cinema—were never actualized, yet his genius pervades in the work of his contemporaries.

Funnily enough, his own feature debut CLOSED VISION might be the film with the clearest narrative to come out of the Lettrist Movement. A consciousness collage in the style of James Joyce, CLOSED VISION works its way from a series of disparate images into a straightforward denouncement of cinema’s calcified classical form. At the time of its release, the film was praised by Luis Buñuel and Jean Cocteau, who called it “the most important experimental work since his own BLOOD OF THE POET.”

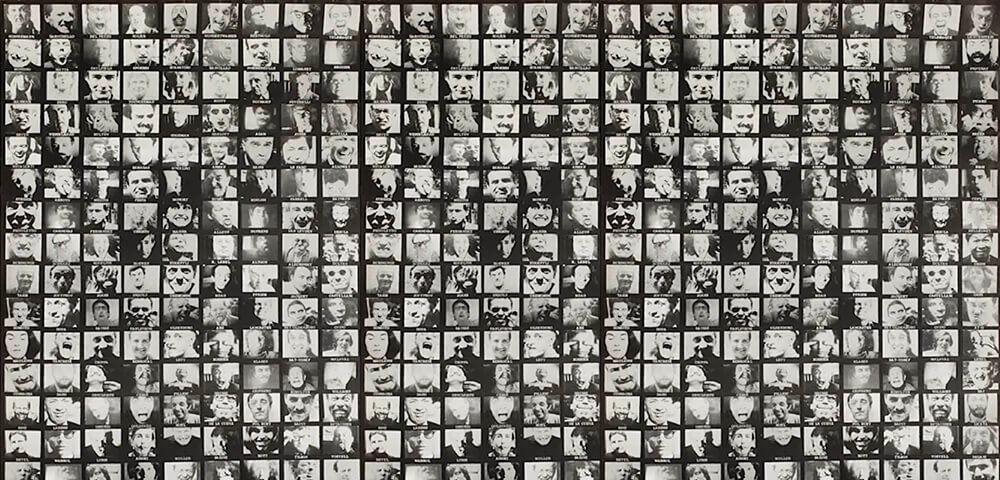

GRIMACE

dir. Erró, 1967

France. 45 mins.

Gibberish.

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 30 – 5 PM, this event is $10

“GRIMACES is just what it says: grimaces. You see 180 internationally known artists making faces. The soundtrack is Lettrist poetry.” –Jonas Mekas

The Icelandic artist Erró’s GRIMACE was made over several years as he toured the globe snapping vignettes of famous artists. Edited together with a Lettrist poem in which Erró phonetically plays around with each artist’s name as its soundtrack, the film becomes a meditation on stardom and identity. Warping and renegotiating the relationship between the viewer and the celebrities on screen, GRIMACE’s simple premise proves effective.

Special thanks to RE:VOIR, Light Cone, Barbara Wolman and Hedy Wolman, Cristina Bertelli, Marc’O, Ed Halter and Thomas Beard at Light Industry, Julia Curl and Robert Schneider at the Film-Maker’s Cooperative, Connor Keep, Steve Macfarlane, and Isaac Hoff.