Between 1946 and 1990, the only production company in the German Democratic Republic was the astoundingly prolific DEFA (Deutsche-Film Aktiengesellschaft). Based in Potsdam at Filmstudio Babelsberg, where the legendary production company UFA had made films throughout the Weimar and Nazi periods, DEFA made it its mission to reclaim the studio from its fascist past. In addition to numerous biopics of illustrious figures in the history of German class struggle, from Martin Luther to Ernst Thälmann, the studio also produced a series of Westerns, known locally as Indianerfilme due to their principle of portraying Native Americans as the heroes in a centuries long struggle against Euroamerican colonial rule. There were twelve such films, all produced between 1965 and 1983, and shot in Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Romania, the USSR, and Cuba. Most of them were produced by the Arbeitsgruppe Roter Kreis, a collective that included directors Josef Mach, Richard Groschopp, and Gottfried Kolditz, who are responsible for the three titles in this series: THE SONS OF GREAT BEAR (1965), CHINGACHGOOK: THE GREAT SNAKE (1967) and APACHES (1973).

The history of portrayals of Native Americans in cinema does not give much cause for pride. James Fenimore Cooper established the canon of Native American stereotypes in his 1823-1841 series of frontier novels, and Hollywood adopted them wholesale for the classic “taming of the frontier” storylines of its Westerns. From the 1920 adaptation of The Last of the Mohicans onward, through 1956’s THE SEARCHERS all the way to the 2013 remake of THE LONE RANGER, starring Johnny Depp as Tonto—complete with mystical inclinations, reduced grammar, and an impenetrably impassive demeanor—the image of the mysterious and vicious yet sage and holistic Indian has thrived in Hollywood. DEFA’s Indianerfilme are certainly not free of stereotypes (especially in the case of the white settlers, who comprise a largely undifferentiated mass of sweaty, sunburned, whisky-guzzling racists), but their portrayal of various American Indian tribes are well-researched and sympathetic. Whereas American films tend to liberally mix various aspects of the dress, dwellings, and rituals of widely differing tribal cultures into completely invented tribal identities, the East German Westerns each focused on a different tribe—the Delaware, the Dakota, and the Apache in the case of the three films in this series.

American Indian scholar and activist Ward Churchill has pointed out that one of the ways in which Western narratives achieve their reduction and flattening of the history and contemporary reality of Native Americans has been by restricting the period and geographical area they cover to the Great Plains between roughly 1825 and 1880. DEFA’s Indianerfilme sometimes break away from this mold, but most often fit into its chronological bracket. THE SONS OF GREAT BEAR takes place in 1876 and APACHES in 1837, but CHINGACHGOOK: THE GREAT SNAKE takes place significantly earlier, in 1740. The only film out of the three to portray Plains Indians is THE SONS OF GREAT BEAR, while the other two take place in New Mexico and the Northeast. Undermining the East Germans’ achievement somewhat is the fact that these films still fit well into the established mold of portraying Native American life only in relation to the Euroamerican presence, never granting them a pre-colonial existence.

In much the same way that the Revisionist Westerns of Sam Peckinpah, Robert Altman, and Arthur Penn were Hollywood’s autocritique of its own conventions, the Indianerfilme were a response both to Hollywood and to West Germany’s brand of the Western. Hugely popular in the 60s, these films were based on Karl May’s novels, which themselves constituted a cultural legacy shared by both the East and the West. Gerd Gemünden has pointed out that the Indianerfilme themselves adopt the “noble savage” stereotype relied on by May, and that their critique of primitive accumulation stems from May’s romantic anticapitalism. This shared legacy is one of the things that points to a dialogue between East and West German cinema—one that is too often dismissed based on the perceived isolation and ideological blindness of East German culture. Eastern and Western productions often used the same Yugoslavian locations and extras, and East German audiences could see West German Westerns by traveling to Prague. The Indianerfilme have even been described as the East German equivalent of the New German Cinema, insofar as they were a reappropriation of a popular prewar form that had until then been used for reactionary or conservative purposes. Much in the same way, then, that Fassbinder adopted the melodrama to remove provocative themes from the exclusive purview of a difficult, rarefied, and elitist art cinema, so the Indianerfilme demonstrated that an effective critique of the logic of capital can be mounted through a form that is engaging, heroic, and naïve. A dramaturg at DEFA, Günter Karl, said that even though the Indianerfilme had to set themselves apart from capitalist films of the same genre, they would have to “use at least part of the elements that make this genre so effective, elements which are not devoid of a certain attraction and—as far as the Indians are concerned—a certain romanticism.”

With this series, Spectacle hopes to contribute to an understanding of the Indianerfilm as a form of radical cinema that—despite having been financed by a massive bureaucratic state—articulates a critique of industrialization and the myth of “progress” in general, whether in their capitalist or socialist form. By programming further series of East German films with the help of the DEFA Film Library at UMass Amherst, Spectacle will continue to battle against Western triumphalist notions of Eastern Bloc culture as more ideologically determined than its liberal capitalist counterpart.

Special thanks to the DEFA Film Library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst

THE SONS OF GREAT BEAR

a.k.a. Die Söhne der großen Bärin

Dir. Josef Mach, 1966

German Democratic Republic, 92 min.

In German with English Subtitles.

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 6 – 7:30 PM

TUESDAY, AUGUST 19 – 10:00 PM

SATURDAY, AUGUST 30 – 7:30 PM

Opening on the Great Plains in 1874, THE SONS OF GREAT BEAR is the only of the three films to take place within the temporal-spatial framework of the “traditional” Western, with the U.S. government encroaching on the lands of the Dakota people. After gold is discovered to be in the possession of Mattotaupa, the chief of the Bear Clan, the unscrupulous settler Red Fox (not of Sanford and Son fame) murders him for refusing to reveal its source. His son, Tokei-Ihto (played by the prolific Gojko Mitić), then launches a series of skirmishes against the white settlers, which culminates in a proposal of negotiation from the local authorities. With the guarantee of diplomatic immunity, Tokei-Ihto agrees to meet with them. Though guaranteed their ancestral lands by treaty, the local government proposes to relocate the Bear Clan (of the Dakota tribe) to a barely arable stretch of land within a reservation. After rejecting these new treaty terms, he is imprisoned and his clan is attacked and forcibly relocated. After escaping from custody, with the knowledge of what treaties mean to the white man, Tokei-Ihto then leads what remains of his clan north, to the fertile areas beyond the Missouri.

In a speech, delivered during a 1998 screening of the film in Seattle, Ojibway tribe elder Richard Restoule said, “After everything that has been done to my people, also through bad films, it is good to know that already 30 years ago, people in East Germany began to think seriously how to do things differently.”

CHINGACHGOOK: THE GREAT SNAKE

a.k.a. Chingachgook, die große Schlange

Dir. Richard Groschopp, 1967

German Democratic Republic, 86 min.

In German with English subtitles.

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 6 – 10:00 PM

SATURDAY, AUGUST 16 – 10:00 PM

MONDAY, AUGUST 25 – 10:00 PM

Based on The Deerslayer, the last installment in the frontier adventure pentalogy that James Fenimore Cooper wrote between 1827 and 1841, CHINGACHGOOK: THE GREAT SNAKE once again showcases the talents of Gojko Mitić, the Serbian phenomenon who conquered the collective heart of East Germany with his chiseled looks, his athletic physique, and his moral rectitude. The son of a Yugoslavian partisan who fought against Hitler’s troops, Mitić had already acted in some West German Karl May adaptations before moving to the East. Cinema professionals moving from the West to the East was rare enough, and with his antifascist lineage, Mitić had the makings of a great popular idol. Like the chieftains he played, Mitić was also a staunch teetotaler. As a dedicated athlete, he didn’t have to be told about the corrupting effects of European alcohol on the Native Americans to publicly renounce it. As Gerd Gemünden puts it, Mitić was “a role model for children, the dream of teenage girls, … and model citizen.”

CHINGACHGOOK takes place in the years leading up to the French and Indian War of 1854-1863, when the Delaware tribe was allied with the English against the French and the Hurons. Chingachgook, “the last of the Mohicans” (Cooper’s Mohicans are a mixture of Mahican and Mohegan influences), has saved the life of the chief of the Delawares, and has been promised his daughter’s hand in marriage. Following a not-unheard-of narrative device, Chingachgook’s betrothed is kidnapped by the Hurons, and he swiftly slings his rifle over his shoulder and sets off in a canoe. Over the course of his adventure, Chingachgook discovers that allegiance with any of the European powers is foolish, since they all view the Indians as an obstacle to territorial control and stand to profit greatly from their extermination. After British troops attack a Huron encampment, Chingachgook makes it his task to convince the Huron leadership that their true, shared enemy is the European invader.

Not only does CHINGACHGOOK: THE GREAT SNAKE give us the satisfaction of seeing a slew of arrogant, bewigged lobsterbacks get the civilization knocked out of them with rifle butts, but it also subverts European domination on a formal level by relegating James Fenimore Cooper’s white protagonist, Leatherstocking, to Chingachgook’s sidekick, reversing the original power relation between them.

APACHES

a.k.a. Apachen, a.k.a. Apachen: Blutige Rache

Dir. Gottfried Kolditz, 1973

German Democratic Republic, 94 min.

In German with English subtitles.

SATURDAY, AUGUST 2 – 10:00 PM

SUNDAY, AUGUST 10 – 5:00 PM

TUESDAY, AUGUST 19 – 7:30 PM

Gojko Mitić returns as Apache chieftain Ulzana, bent on “bloody revenge” (as suggested by the German DVD title) against a band of white industrialists and their henchmen. Although the events of the film suggest that Mitić’s character is actually based on Mimbreño chief Mangas Coloradas, Ulzana was also a famous chieftain who led raids through New Mexico and Arizona in the 1880s, famously portrayed in Robert Aldrich’s unsympathetic (i.e. “complex”) 1972 Revisionist Western, ULZANA’S RAID.

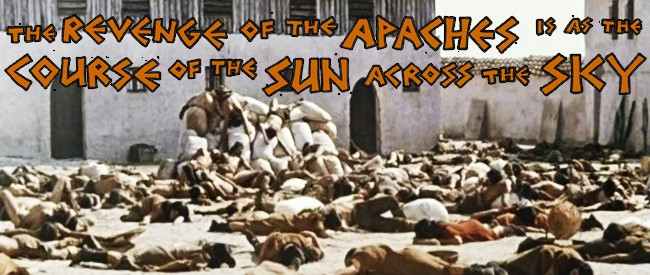

Whereas the action of THE SONS OF GREAT BEAR starts with the discovery of gold, this time, the coveted mineral is copper. Near Santa Rita, New Mexico, the local Mimbreños have enter into a contract with a Mexican mining company that promises them continued use of their hunting grounds in exchange for safe passage for the company’s convoys. This arrangement has already robbed the band of its self-determination (“Remember the tales of life before the White Man? We lived well without relief flour”), and in any case it can’t last. An American mining company wants in on the profits, and the Mexican government has put a price on Apache scalps: $100 for a brave, $50 for a squaw, and $25 for a child. The “White Eyes” arrive in Santa Rita to arrange the total subjugation of the Apaches with the help of the local administration. As the mining company’s engineer explains to Santa Rita’s meek collaborationist sheriff, “There is no doubt that the directors want more copper and fewer Apaches.” The atrocity that sets Ulzana and his band on the warpath takes place during the annual distribution of relief flour, when 400 Mimbreños are collected in the town square. An army cannon is suddenly uncovered and fired into their midst and the survivors are systematically massacred by grinning, whisky-swigging Americans who callously tally up their scalp totals. Ulzana witnesses this bloodshed and, narrowly escaping, swears to his companion, “The revenge of the Apaches is as the course of the sun.”

APACHES is satisfying both as a tale of indigenous vengeance against an imperialist invader and as a well-crafted adventure film. Mitić’s horseback acrobatics and dextrous archery are a delight to behold, and the Mimbreños’ lamentations over their lost way of life are sure to make all but the most hardened hearts yearn for a life before—or after—capitalism.