The film career of Franky Schaeffer has largely faded from public mind, but nonetheless remains a curious and inscrutable chapter in ‘80s genre B-movies. Francis “Franky” Schaeffer, Jr. grew up as the son of noted Evangelical theologian and pastor Francis Schaeffer, known as the founder of the Swiss alp spiritual center L’Abri in 1955, an influential philosophy seminar and commune hybrid that attracted bohemian spiritual seekers and rigid neo-Calvinists alike. A lover of Christian art and texts, Schaeffer Senior honed a strict presuppositionalist approach to theology and ethics, developing a worldview highly cautious of attitudes and art trends he deemed “post-modern” (especially directing his ire towards John Cage and Andy Warhol, et al), meanwhile preaching a brand of Christian Reconstructionism that sought to reinvigorate evangelical participation in official state politics.

In the years leading up to Ronald Reagan, Schaeffer Senior was a critical figure in the burgeoning Protestant Right—particularly on the issue of abortion, which prior to his influence was primarily the domain of the Catholic Church. With the help of former White House chaplain, and personal spiritual counsel to born-again Gerald Ford, Billy Zeoli, Schaeffer Senior was able secure funds (in part from Amway billionaire Richard DeVos) to adapt his book and lecture series HOW SHOULD WE THEN LIVE? into a 10-episode television show directed in part by his then-25-year-old son Franky. (It was post-produced by evangelical pastor Mel White, later an out gay man and LGBTQ advocate, as well as father of SCHOOL OF ROCK scribe Mike White.) The program was a history of Western civilization told from the Christian point-of-view, designed to assert the necessity for a new dominion; and indeed, it did fire up a young generation of right-wing Jesus freaks, among them Tea Party firebrand Michele Bachmann who noted it as a core influence. Later, in 1979, Schaeffer Senior co-penned a notorious anti-abortion screed titled Whatever Happened to the Human Race?—conspicuously, with soon-to-be Reagan Surgeon General D. Everett Koop.

Following his TV show production credit, Schaeffer Jr.’s interest in the entertainment industry would only grow. In 1981, the aspiring filmmaker penned a fascinating diatribe titled Addicted to Mediocrity, drawing in part from his rigorous education at L’Abri. He argues that Christian art once reigned supreme in craft and complexity but was by the 20th century losing out to secular artistic endeavors, and that it was up to a new generation of Christians to re-emphasize cultural production. Schaeffer Jr. imagined a world in which dyed-in-the-wool conservative Christians would make prestige art on par with Fellini and Bergman, a culture war with its eye on capital-C culture.

The films he eventually made were perhaps another story. Shortly after his father passed away three years later, in 1984, Schaeffer Jr. distanced himself from the ministry and cancelled further speaking engagements, instead burrowing himself on the edge of the film industry with hopes of making elevated sci-fi films on par with A CLOCKWORK ORANGE, BLADE RUNNER, or REPO MAN. Reception was poor. One former devotee, inspired by Schaeffer Jr. to continue to soldier on in the film world despite it conflicting so drastically with his evangelical life, wrote in the LA Times: “Yes, I was indeed “blown away” by WIRED TO KILL. That someone as literate as Schaeffer could write such a dull-witted and thudding rehash of tired old themes and then presume to pass this off as a committed Christian making a philosophical statement is appalling.”

For Christians, the films weren’t explicit enough; for audiences at the time, they were simply mediocre. But for Spectacle’s audiences, watching now with over three decades of hindsight, these films might reveal something else. They are a snapshot of a religious right refuge in the thick of the Reagan years, capturing Schaeffer in increasing doubt before he left Protestantism entirely and disavowed his politics. (He was a diligent Obama supporter, appearing as a talking head on network news often in the ‘00s; today he describes himself as a “Christian atheist” and is affiliated with the Orthodox church.) They’re crypto-Christian oddities, unsure of whether they want to ooze into the pop-cultural membrane as popcorn action flicks or philosophizing high art. But most of all, they’re pretty good B-movies, filled with good bad synth leads, suspect practical FX, set pieces pulled off to varying degrees of success, and of course the schlock and sheen of the Me-First decade and its discontents.

WIRED TO KILL (a.k.a. BOOBY TRAP)

Dir. Francis Schaeffer, 1986

96 min, USA

THURSDAY, AUGUST 04 – 7:30 PM

MONDAY, AUGUST 08 – 7:30 PM

TUESDAY, AUGUST 23 – 10:00 PM

SATURDAY, AUGUST 27 – 10:00 PM

Taking place in an alternate 1998 in which famine has transformed society into a wasteland of miscreant gangs and deindustrialized clutter, Schaeffer was perhaps trying to channel ROBOCOP (one particularly Verhoeven-ian throwaway gag has a hospital dispatcher reminding patients that if they wish to sue their doctor, there’s a round-the-clock toll-free number) but instead taps more into the proto-militia movement survivalism of John Milius’s RED DAWN. Steve (Devin Hoelscher) lives a quiet life with his law-abiding suburban family, moonlighting as an electrical engineer in his spare time, toying with primitive robotics and perfecting his own synth pop rig. When a gang murders his family and leaves him legless, he and Rebecca (Emily Longstreth of PRETTY IN PINK) conspire to exact revenge. Per the film’s seething tagline—“If you want to make history, you gotta make your own”—it’s got a creeping soft Nietzschean undertone that might pass for Christian allegory. Co-produced by future Christian right-wing radio personality Paul McGuire. Schaeffer says he “laced” WIRED TO KILL “with what [he] would describe as small Felini tributes”… but if you can guess how or where, you deserve to be refunded the price of admission!

HEADHUNTER

Dir. Francis Schaeffer, 1988

91 min, USA

TUESDAY, AUGUST 02 – 10:00 PM

FRIDAY, AUGUST 12 – 11:55 PM

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 17 – 7:30 PM

SATURDAY, AUGUST 27 – 7:30 PM

Schaeffer’s first with Gibraltar Entertainment, the ‘80s cheapie studio headed by VALLEY GIRL writer Wayne Crawford, HEADHUNTER follows cop Pete Giuliani (Crawford) as he trails a voodoo ritual serial killer who has beheaded a Nigerian immigrant in Miami. (In actuality, it’s South Africa, which leads to roughly the same feel as RUMBLE IN THE BRONX’s Vancouver-Bronx). As many reviews have noted, the movie attempts to fuse its cop-procedural-slasher with a rather ‘deliberately paced’ domestic drama, as Giuliani is coping with a recent divorce due to his wife taking a female lover—a reminder that Ari Aster didn’t invent melodrama-occult-horror hybrid. Notable is its climax, which juxtaposes the final encounter with the killer with a television broadcast of THE HIDEOUS SUN DEMON.

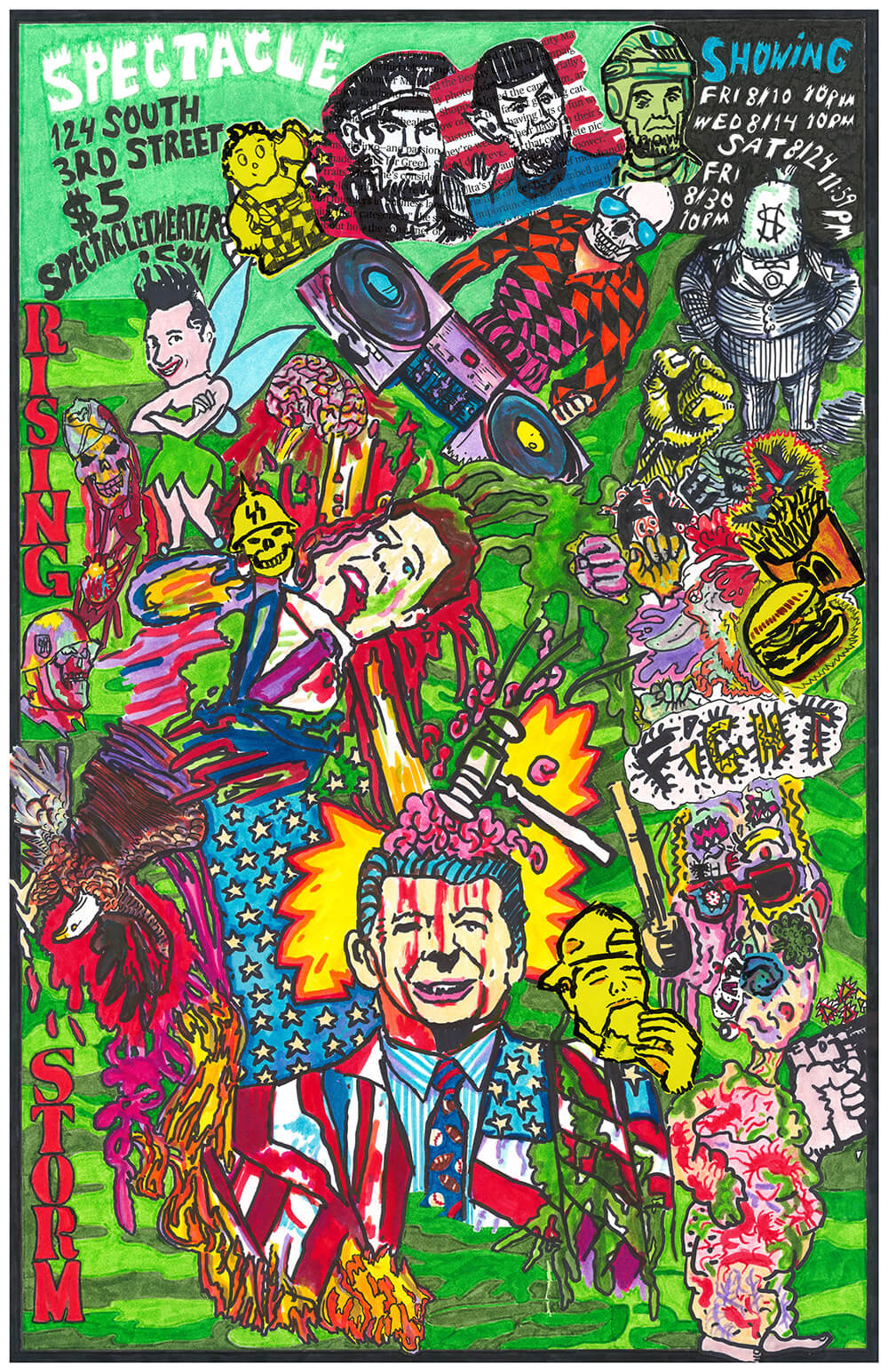

RISING STORM (a.k.a. REBEL STORM, a.k.a. REBEL WAVES, a.k.a. SHIP OF THE DESERT)

Dir. Francis Schaeffer, 1989

95 min, USA

FRIDAY, AUGUST 05 – 10:00 PM

SATURDAY, AUGUST 13 – 11:55 PM

FRIDAY, AUGUST 19 – 7:30 PM

WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 31 – 7:30 PM

Made in the thick of several high-profile televangelist scandals (Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart in quick succession), RISING STORM imagines a world in which the bunk TV preachers have taken over, a zany Terry Gilliam-esque dystopia of Reagan-Bush proportions. It’s 2099 in Los Angeles and Joe (Gibraltar’s Wayne Crawford) has just gotten out of prison, reuniting with brother Artie (Zach Galligan of GREMLINS). America has become some sort of post-nuclear barren wasteland crossed with the twin influences of supreme spectacle (WWE wrestling and archaeological digs for ‘80s pop culture ephemera) and biblical repression (citizens are allotted one act of intercourse a month). The brothers lead an underground resistance against the tyrant president Reverend Jimmy Joe II, teaming up with a pair of affable blonde women. Schaeffer’s most cynical—and personal?—film, it’s relentlessly down on the merchandise frenzy and mediatized religious fervor of the late ‘80s.